The August 2021 Expedition

The August 2021 Expedition Team consisted of eight CCR divers, four American and four European: Rick Ayrton, Andrew Donn, Jacob MacKenzie, Joe Mazraani, Steve Pryor, Scott Roberts, Rick Simon, Joe St. Amand. With the exception of Donn and St. Amand, the team had dived together previously as part of an expedition to Britannic in May of 2019. Roberts led the Britannic expedition, which made news around the world for the discovery of the ship’s bell. Lusitania was a natural follow up. Mazraani and Roberts, by now not only dive teammates but close friends, co-led the expedition to Ireland. Every member of the team recognized the role that the sinking of the Lusitania played in both British and American history.

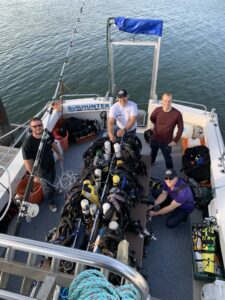

The team lived and worked out of Kinsale, a small seaside town on Ireland’s southern coast. Divers traveled to Lusitania aboard Captain Gavin Tivy’s vessel, Sea Hunter. Tivy is a diver and an experienced captain. Sea Hunter has been instrumental in assisting the Irish government, under strict permits and archeological protocols, with the retrieval of artifacts from Lusitania and other historic vessels in the area.

The Dives

The team made six dives to the wreck: two in the forward section, three amidship, and one in the stern. They were joined by Diver Eoin McGarry on two of their dive days. McGarry has dived Lusitania more than any other person alive and worked closely with Gregg Bemis to ensure the wreck’s memory and history are preserved. Prior to his death, Bemis appointed McGarry one of four Lusitania stewards. Today, McGarry serves an ambassador to the wreck to the diving and non-diving world alike and works alongside a team at the Old Head Signal Tower Committee, which now owns the wreck, to monitor Lusitania expeditions and to oversee efforts to preserve the ship’s legacy. The Committee’s most pressing project is to build a museum at the Old Head of Kinsale to house Lusitania artifacts and historical documents. McGarry was with the team for their first and last dives to the wreck.

Descending on Lusitania is at once thrilling and disorienting. Unlike shipwrecks that rise up in identifiable chunks from the ocean floor, Lusitania is a collection of scattered wreckage and debris. This is due not only to U-20’s torpedo, but to British Navy depth charges and the 1980s salvage. Natural conditions have further contributed to the wreck’s deterioration. Lusitania has been battered by the North Atlantic’s notorious currents, tides, and constantly shifting sands. There are larger places where divers can penetrate the wreck and explore interior compartments, but the allure of diving this wreck is hunting for signs of life in hidden amongst the debris.

Each section of the ship has unique features. Lusitania’s forward section includes remnants of the bridge, the area from which Captain Tuner and his crew operated the liner on its final voyage. Here, large items used by the captain and his men are frozen in time. The telemotor helm, part of the hydraulic system used to the steer the ship, is visible. It was used to transmit commands to the steering engine and turn the ship’s rudder. This section of the ship is the final resting place of Lusitania’s enormous triple-chime steam whistle. It is the one that sounded when the ship left New York for the last time.

The damage to the vessel is most evident amidship, just behind the bridge, where the torpedo struck. Here, in addition to a large debris field, there are some more structurally substantial areas, places where divers can go inside the wreck and explore. The boilers are located amidship. They have been the focus of debates about whether a ruptured boiler caused a secondary explosion that hastened Lusitania’s sinking. Getting to the boiler area requires divers to penetrate an interior compartment. Lusitania had 23 double-ended and two single-ended boilers situated in four boiler-rooms. Only a small portion of those boilers are visible. The rest are buried too deep within in the ship to make it possible to know how many are still intact and if any exploded. Remnants of passengers and crew are also evident amidship. Ornate windows, portholes, and chamber pots are caught in sprawling piles of debris.

The team’s last dive was their one and only dive to the stern. It turns out that last dives are magical for this team. It was on the team’s sixth and final dive to H.M.H.S. Britannic that Joe Mazraani discovered the ship’s long-lost bell; and it was on the last dive to Lusitania that diver Rick Ayrton contributed to her history. Ayrton came across what at first appeared to be a large piece of metal or wood. He realized upon further inspection that it was a large piece of glass covered by a thin coating of sand. Beneath the sand, he saw small patches of bluish-white peeking through. He fanned the sand away to reveal larger blue sections and photographed what he could before it was time to turn the dive. Ayrton assumed someone had seen this panel before, but he was wrong. Lusitania scholars could only speculate what it might be based on photographs and ship’s plans. It took the following expedition to document the piece further and provide enough evidence to determine that what Ayrton found was a blue glass door that once graced the second-class smoking room. This is an important example of how expeditions build on one another and how each small observation contributes to the ongoing exploration of this magnificent shipwreck.